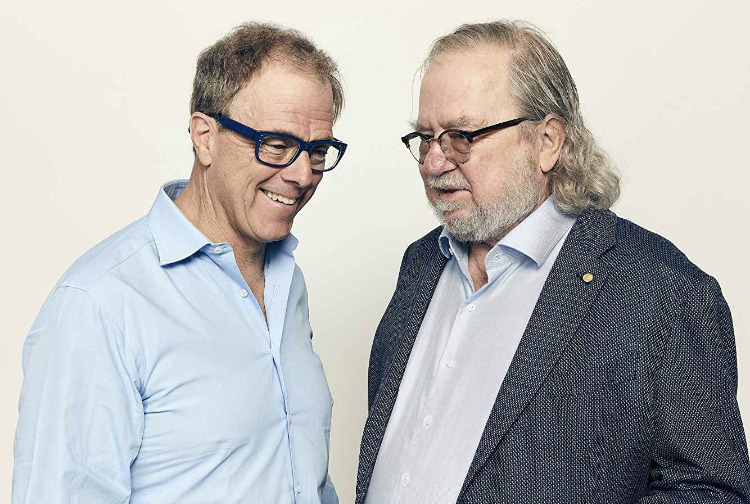

“Jim Allison: Breakthrough” is Bill Haney’s new fascinating documentary on the brilliant and colorful scientist Jim Allison and his quest to find a cure for cancer. Allison won the Noble Peace Prize in 2018 for discoveries in cancer immunotherapy and creating an antibody that would enhance the ability of the immune system to battle cancer. But for decades Allison fought a lone battle and struggled against the skepticism of the medical establishment and the resistance of Big Pharma. Woody Harrelson serves as the perfect narrator for the story of a maverick scientist.

Director Bill Haney is an incredible man, himself. Not only a filmmaker, Haney is also an inventor and an entrepreneur. As a freshman in college, Haney invented an air pollution control system for power plants. He has founded over a dozen tech companies. Currently, Haney is the co-founder and CEO of Dragonfly Therapeutics, a biotech company developing drugs to cure cancer, and co-founder and CEO of Skyhawk Therapeutics, a biotech company developing drugs to cure Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. As a screenwriter, director, and producer, he has made 15 narrative and documentary films.

MUSE TV & Culturally Obsessed’s Jennifer Ortega was thrilled to speak with Billy Hanery not only about Jim Allison and Breakable but about his life as well.

Becoming a Filmmaker

Jennifer Ortega: Not only is Jim Allison amazing, but you are incredible! You have all these different facets. How did you get into filmmaking? I know you went to Harvard and you’ve been heavily into environmentalism. Did you always want to do documentaries to bring awareness?

Bill Haney: I’ve always been interested in how you make society better. My instinct towards that was always with science and technology. I would say that’s kind of the path I’ve taken. If there’s been a consistent path at all, that’s been it. I love stories and have always appreciated storytelling, but I wasn’t planning to become a storyteller. My first experience with film honestly, was because my mother made me make one.

JO: Really?

BH: Yes, I was running a tech company that had invented systems for cleaning up nuclear waste at nuclear waste labs. I was let’s say 30 years old. I never made a film and never been to class in filmmaking and had no experience with it of any kind except viewing film. I got a phone call from my mom. I grew up at a monastery in Rhode Island run by Benedictine monks. My parents were teachers in the school that they had and we lived on the campus. Across the street from us was a Portuguese American man who as a 14-year-old had moved in with an elderly woman and became her gardener. Over a long period of time, he became a gifted gardener and then a celebrated gardener. And my mother’s best friend was his wife.

So I got a phone call from my mom and she said I have a favor to ask. And I said sure, what is it? And she said promise me you’ll do it. And I said but what is it? She said I’ve just been to see Mary, the gardener’s wife, and George is dying of cancer. We had several hours together and as I walked out I asked Mary if there’s anything I could do to help her. She said George only has one thing he wants. There was a documentary filmmaker who came and filmed him several years ago, but nothing’s ever happened since. The last thing he wants to do before he passes away is to see the film. And my mother wanted me to make that film. I said but I don’t make films. And she said you’ll figure it out. I asked her do you know who the original filmmaker was or any facts of any kind? She said you’ll figure it out. I got to go. Slowly, I tracked down that it was Errol Morris. I finally found him and got him on the phone and said do you know George Mandoza, the topiary gardener? He said years ago, but I’m done with that. And I said yeah that’s not going to work. So my role was extremely limited and not creative. It finding out what was required to finish that film and over time we figured out what that would be. That was my first experience with film.

Then I was with the world’s last undisturbed gray whale nursing lagoon. It is in Baja Sud, on the western edge, two thirds the way down the peninsula. I went with the head of the natural resources defense council because Mitsubishi Chemical was planning to build the world’s biggest chemical factory inside the last gray whale nursing lagoon on Earth. We went to try to stop them. We drove to Tijuana and flew old like a 1930s old plane, landed on the sand in the sandbanks in this twenty-five hundred square miles desolate landscape. And after five or six days camping there, we were drinking tequila by the fire there one night and there were like eight of us there and somebody said someone’s got to make a movie about this and the last person to say not me was me. And that became the first movie I directed.

JO: It’s like you picked the short straw, but that’s incredible!

BH: So that’s how I got into filmmaking.

JO: I love that because everybody thinks you have to get into filmmaking one way and there’s no one way. Everybody has their own path to it.

BH: That’s right.

Meeting Jim Allison

JO: I can’t believe I didn’t know about Jim Allison. Such a fascinating guy. I was so glad you made this. How did your paths cross?

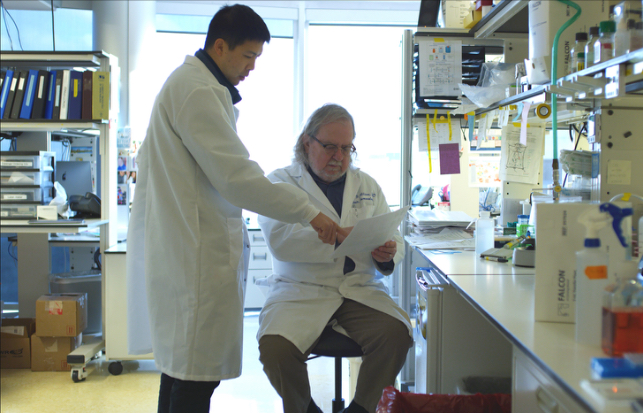

BH: Well a couple of ways. First, as you know I run two biotech companies, but Jim’s scientific work which launched the field of immunology is focused on T cells. They are essentially in two parts, the adaptive immune system, and the innate immune system. And Jim created the field and launched essentially Gen 1, which was T cells in the adaptive immune system. I had started the company in what I think will be demonstrated to be Gen 2 which focuses on what are called natural killer cells and at the centerpiece of the unique immune system. So scientifically I was very familiar with his work. And the good news is that his work is clear and the bad news is that you can see in the graphics at the end, the good news is 20 percent is curing & the bad news is that 80 percent is not. So I’m working on the 80 percent. So I was familiar with his work for that reason. And then in terms of wanting to do a film on this subject, I think there were three big motivators for me. The first was that the classic documentary film that isn’t a celebration of an artist or a person. A feature film has got fairly natural good guys and bad guys. You know it’s a Nobel Peace Prize winner versus the sadistic killers. And I’ve made those films too. And I think that they’re valuable and interesting. I just don’t happen to think that is what America needs right now. So in our highly polarized society, I was trying to find a story that united everybody. Pick something we can all agree on to become that prism. And one thing you could say about cancer is that nobody’s for it.

JO: Absolutely.

BH: So since we can all agree we want cancer go away and sad to say almost everybody’s family has been touched by cancer.

JO: Yeah, I can’t think of a person I know that hasn’t, honestly.

BH: So we now have a thing we feel the same way about and we’re emotionally connected to. I thought that would take us into a place where we could talk about things t and celebrate the creative life that that is so infrequently celebrated in America. You know we’re so celebrity oriented and our definition of creative leaders is so focused on you know one part of society.

JO: One very superficial part of society. It’s funny because I was just talking about that in the other room how people aren’t passionate about anything, they just want to be famous.

BH: I don’t even know why.

JO: I don’t why either.

BH: Does it look like famous people are having a lot of fun? It looks miserable. I think privacy is like your health. You don’t miss it till it’s gone.

JO: Absolutely.

BH: It’s a world where people essentially give off shards of their privacy in return for temporary adulation. It seems self-loathing.

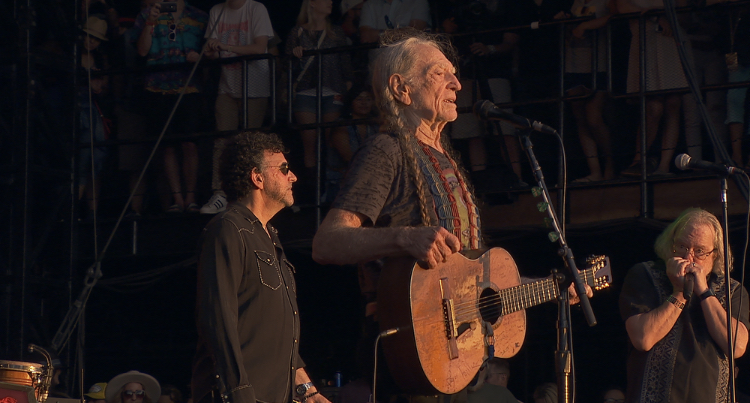

JO: Yeah it’s so fleeting and just seems awful. I love Jim because he’s so unconventional. He’s kind of like the punk rock version of a scientist. I think that’s really great into reaching a broader audience. I think documentaries on science or medicine, people, in general, have this idea of that it will be boring. Now that has changed a lot. I’ve always loved documentaries and there’s a lot that people maybe are not so familiar with that kind really fight that idea.

BH: Well, the thing about documentaries is they that come essentially in two colors. Exposition docs are that way. You go to get your left side of your brain engaged and that’s fantastic. There’s nothing wrong with that. And we all enjoy that. Me too. Feature docs are really a lot more about your heart than your head. In an ideal world, you get both, but they are much less common. They’re growing I think in impact and I think personally that at least the grown-ups among us have had enough of it’s all about superheroes who you know were infected by radioactive something. Not that I’m against that at all. I’m glad for the kids to be doing that. And I don’t mind an hour and a half of it if I’m on an airplane, but I think that that being the modus operandi within this cultural moment is a bit goofy.

JO: It really is. My heart is always with indie filmmaking, whether it’s a documentary or narrative or whatever because it’s more interesting. I always think you know you can’t get strange, more interesting stories than actual truth which is why I like documentaries. Even Jim’s whole story. Like his upbringing and everything is so interesting to me. I’d rather watch that any day than like Iron Man 20.

BH: That makes you 1 percent of the population.

Laughter

BH: The world’s coming to you I think. The last film I did, we shot with Bobby Kennedy. And he used to say America is on a path to being the most over entertained and under-educated society in the history of the world.

The Takeaway of the Film

JO: What do you hope that audiences will take away or maybe share with other people?

BH: Well I think ultimately what I want them to do is to be inspired and to find the film dramatically engaging, joyful and raw, which I think it is. And it’s surprising, in the world of science what we think we know about isn’t the scholar or the dry desiccated planetary system that is expected. It can be all kinds of joy and irreverent rapscallion behavior. And that’s great too. And so that’s what I want people to say when they see the film. And now I would be less than straightforward if I said I don’t also want young folks who want to have a creative life and who want to push back against the wall of existentialism that all of us consciously want to do. We want our lives to have meaning. We want to feel like it mattered.

And to do that we have to do things that are distinctive and genuine, rooted, purposeful creativity, not just stripping in the public square because people pay attention for 10 seconds. but actually having a purpose bigger than yourself that is linked to your creativity and doing in a sustainable way.

JO: So leaving a legacy. Leaving something that actually means something.

BH: I think there’s just more opportunity for them to do that in the sciences. I completely understand and celebrate their desire to be creative. I just want them to know that there are more paths. I don’t want them to feel that they all must become actors or they all must become poets or they’re stuck. You can see in Jim’s work, but also the other scientists that are there. Not all of them are celebrated. Not all of them have a noble prize, but they all are actually doing purposeful work that they can be proud of and engage with and that’s part of it. And it’s team-oriented. It’s not some isolated, lonely, distant experience for them.

Breakthrough is currently playing in select theatres. https://www.breakthroughdoc.com/